“When I’m finished, there’ll be no treason even whispered in Ireland for the next 100 years.”

–General John Maxwell, British Army

Thursday, May 4, 1916

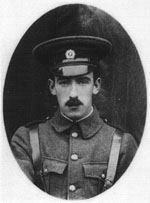

Soon after midnight, Ned Daly received a visit in his cell from sisters Kattie Clarke, Madge and Laura. Though given a permit for allowing only one to visit, the three remained locked together as though chained, unshakable in their resolve to see their condemned brother together. None of the soldiers opposed them. Kattie told Ned that her Tom had been shot the previous morning, and that their Uncle John, Tom Clarke’s prison mate for 11 years, regretted not being able to join him. Impressing the guards with their composure, not even crying let alone fainting, the three young women bade their brother goodbye. On their way out they met the sisters of Michael O’Hanrahan, who were under the illusion their brother was to be sent to England. When Eily O’Hanrahan demanded further information regarding this, a soldier announced their brother, along with three others, was to be shot at dawn.

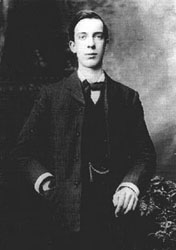

That same night, in yet another moldy cell—smelling of old urine and lit by a single candle—Mrs. Pearse told her surviving son Willie that their Pat was dead. Willie proudly told her that at his own court martial he’d made no attempt to deny his participation in the Rising. The brothers inseparable since toddler years, Mrs. Pearse knew Willie had to follow once again the older brother he idolized.

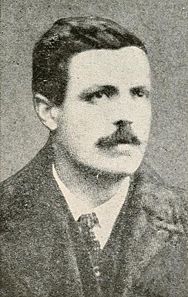

At 2 a.m., Grace Gifford Plunkett was allowed 10 minutes to visit her husband of two and a half hours. A soldier-guard checked his watch. Grace had noticed the faces of the soldiers at Kilmainham—some barely old enough to shave, many of them Irish. All were participating in a greater movement, as the work of so many—often at disparate activities—can coalesce to run a great ship or to operate a railway. Only this combination of tasks led not to the movement of trains, or of a vessel over thousands of miles of ocean, but to the execution of a dying man, a young poet.

A Captain Kenneth O’Morchoc was assigned to lead the firing squad. He asked to be excused from the duty, as he and Joe Plunkett had played together as young boys. The commandant assented.

As dawn approached, four Capuchin friars arrived in an automobile. Father Columbus was assigned to administer to Ned Daly, hoping to be more effective than the day before, when he’d asked for final repentance from Daly’s brother-in-law, Tom Clarke. The older Father Augustine—of generous size, beard and disposition—was assigned to baby-faced Willie Pearse. Father Sebastian would accompany Joe Plunkett to the Stonebreakers’ Yard—as Father Albert would for Michael O’Hanrahan.

As another new sun began its dispersal of purple-gray gloom, four volleys—minutes apart—rang out, each quickly followed by a single pistol shot. Soon after—through streets of the awakening city—a motor-truck again lumbered, enroute to the quicklime pit. Already newsboys were leaving the Irish Independent and the London Times on doorsteps, as columns of breakfast-fire smoke drifted into a sky growing lighter by the minute.

In the early afternoon, another wave of rebel prisoners was assembled at Richmond Barracks for transport to internment in England. For those not inclined toward martyrdom—comprising the vast majority of the rebels—it meant a reprieve from sure death. Among those preferring to continue living to fight for Ireland another day were Sean McDermott and Michael Collins. When it appeared both would pass muster, a Castle detective, Inspector Burton, recognized the limping McDermott and had him fall out. It meant for him court martial and the firing squad. Collins swore he himself would live to extract his revenge on the gloating Inspector Burton.

Later that afternoon, Major John MacBride went to military trial. Though not an instigator of the Rising, Major MacBride was nonetheless well-known to both the rebels and the British for his leading an Irish Brigade on the side of the Dutch during the Boer War. And he happened to be married to political radical Maud Gonne (longtime recipient of the unrequited love of poet William Butler Yeats). And he’d been a witness at the 1899 marriage ceremony of Tom Clarke and Kathleen Daly in New York. At last England would extract final vengeance against the renegade Major. He was found guilty, as were—that same afternoon—Michael Mallin, Chief of Staff of the Citizen Army and right-hand man of Connolly—and a short time later, the Countess Markievicz.

Friday, May 5, 1916

At dawn, John MacBride, escorted by Father Augustine, was marched blindfolded and handcuffed to the Stonebreakers’ Yard. After a final pistol shot to the head by the officer-in-charge, Father Augustine anointed Major MacBride with the oil of Extreme Unction.

Next to be tried was Eamonn Kent, one of the seven signers of the Easter Proclamation of a Republic. Four of the signers were already in the quicklime pit—along with Willie Pearse and John MacBride, making a total of six.

Sinead de Valera at last gained her meeting with the American Consul. Her husband, Eamon, of Spanish and Irish extraction, had actually been born in New York. She was given hope he would be spared execution. The Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson was already mindful of the effect the executions were having on Irish-Americans—nearly all stalwart members of the Democratic Party. Cardinal James Gibbons, 82-year-old Archbishop of Baltimore (who grew up in Ireland), had raised his concern over the “danger of manufacturing martyrs with senseless executions.”

Reference: Rebels, by Peter De Rosa