Logo of the Brotherhood of Co-operative Commonwealth, the entity behind Equality Colony in Washington state

from Wikipedia

In May of 1898, 16-year-0ld Mike Scanlon travels west from New Jersey to meet up the with his brother Jimmy in Skagway, Alaska, to work on building the White Pass & Yukon Railway. The brief war taking place in the Philippines and Cuba will soon end, leading to a Spanish defeat.

There’ve been signs of recovery from the economic depression–brought on by Wall Street speculation and over-valuing of railroad stocks and real estate–that had been ravishing people’s lives since 1893. Still, the working classes were reeling from five years of wage and job cuts. Many were flocking to the Yukon region to find quick riches in gold strikes rather than continue toiling for what was being increasingly seen as a system mostly benefitting the already “filthy-rich.” Concurrently, the Populist and Socialist movements were gathering up the discontented. An offshoot of the latter was the move to set up Utopian colonies in western Washington state–and even a vision, backed by its governor, to “socialize” the entire state.

Enroute to Seattle, on the train Mike meets 18-year-old Anna Smithson, journeying to meet up with her transplanted New Jersey family at the Equality colony, building along the upper reaches of Puget Sound. Accepting an invitation from the Smithson family to join them at Equality, Mike postpones meeting his brother in Skagway, where gold seekers are thronging before making the arduous trip inland to the Klondike strike along the Yukon, a trip the new railroad promises to make easier–and at the same time making enormous profits for its English investors.

Excerpted from Chapter 3 of Lost Utopia (not yet published), part of an Irish-American epic. Two prequels, Cinders Over The Junction and Beyond The Divide, from Shamrock & Spike Maul Publishing Co., are available in paperback from Village Books, Fairhaven (Washington, U.S.A.), and in paperback and Kindle from Amazon.

* * *

The town of New Whatcom. Washington, had its beginnings as Sehome, seen here in 1889, the year Washington became a state. Centered around Elk Street, the town grew toward the forested background of this scene. By 1898, it was looking more like a city. In 1904, New Whatcom merged with Fairhaven to become Bellingham.

courtesy Whatcom Museum, #2008.57.198

Mike and Anna left under a pre-dawn purple sky for the long round trip to New Whatcom, expecting to return past dark that evening. They angled back across Oyster Creek as it tumbled to Samish Beach below. Cresting the headland jutting out to Pigeon Point, north of the beach, the lake-smooth surface of Chuckanut Bay before them lightened to gray-blue. Sunlight touched the east slope of Lummi Island, rising as twin cones when viewed endwise, and, toward the west, bathed the rounded heights of Orcas. Rounding a hairpin turn and descending to the bay’s edge, hunger overcame them as they followed the sweeping curve of a sandstone-strewn beach. Unwrapping from a towel fried egg sandwiches on colony-baked bread, they passed to each other a fruit jar of still-tepid cereal coffee.

Toward noon they plodded through Fairhaven. Following the trolley line, they reached the hardware store on Elk Street in New Whatcom. Mr. Morse, the store’s owner, oversaw the loading of the wagon with crated sheet-iron stoves. Beginning the return, Mike and Anna stopped at the small hospital in Fairhaven run by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace, to pick up medical supplies from the nuns.

The sun was low over Orcas Island when, hours later, the wagon again coursed the water’s edge. When not talking, they sat easily in each others’ company, close on the high spring seat, their hips touching, Anna taking the reins on the level stretch along the beach where there was no precipitous drop-off. The approaching sunset cast a newly melancholic air, realization sinking in of Mike’s scheduled departure in a few days, a mood till then kept at bay by the brightness of the day and the at-times lively talk—such as contrasting agnostic rationalism with Christian, especially Catholic, faith; on whether or not Karl Marx was correct that socialism went hand-in-hand with an atheistic view of the world; on whether or not the teachings of Christ, with which Anna was thoroughly familiar (having labeled her family as “non-religiously Christian”), were antithetical to the capitalist system of economics. In agreement on this last matter, it had become obvious to Mike that Anna was a “debating society” veteran.

Tying the team to a wind and salt stunted fir tree, they stepped out over sand and sandstone rocks to a short point, formed of boulders and dune-like humps, and sat down on a bleached drift-log, clasping hands. Mike admired how the afternoon northwesterly breeze ruffled her hair.

“You don’t have to go,” she said after an agreeable silence. “You can stay here and be part of…the changes. You do believe we’re ushering in a new and better way to live, don’t you? Do you really want to go to Alaska and work on a railroad being built to satisfy men’s greed?” The response on Mike’s face caused her to further explain. “I mean, isn’t its purpose to make it easier for fortune-hunters to reach the goldfields…and to fatten the coffers of English capitalists?”

While not feeling a need to defend a commitment to go work with his brother Jimmy, Mike felt a pang in seeing twin tear-streams on Anna’s cheeks. When they first met on the train coming West, she’d caught him crying—but until now he’d never seen her cry. Sure, they’d done hand-holding and a little smooching, but he felt a thrill of disbelief as now she clasped her arms around his waist and buried her head against his chest. Could this older girl, soon to be a schoolteacher, actually feel something akin to adult love for him? Her hat had fallen off and he stroked her sand-colored hair. She turned her face up toward his. “I don’t want you to go!” she said, after a sniffle. “You can write your brother. I think he’d understand.” Looking into her upturned face, child-like with tear-reddened eyes, it occurred to him he could do exactly that. Instead of finding his little brother at the Skagway dock, Jimmy would be greeted with a letter. Mike would pay him back the cost of the steamer tickets. Conflicting thoughts fled his mind as their faces converged into a lingering kiss. Distantly hearing the lapping of gentle waves, he felt his hand taking on a life of its own as it began straying over female contours totally novel to his touch.

She gently grasped his hand and pulled it away, breaking the kiss. “No, little boy, no,” she said. “We mustn’t. We shan’t shame ourselves…and dishonor the colony. They trusted us to be together today.”

Feeling chastised, Mike began to stammer an apology. Anna put a finger to his lips. “It’s okay” she said, in a sweet near-whisper. “No need. You’re a good boy…. We’d best be getting back.”

Jouncing along the beachfront road, they soon again relaxed with each other, overtaken by a yet-more-intense euphoria as the sun set. Threading the switchback and crossing the Pigeon Point headland in the oncoming darkness, they made plans. He would be gone for two years, working hard and saving money. He would be 18 when he came back, work-hardened and no longer a boy. They would get married and have a room in Apt. House #2, and later, when they started raising a family, they would be entitled to a lot on which to build a house. He would further expand his skills in the wagon shop, and perhaps learn boatbuilding—and start a new shop. The colony would build boats for its own use, and to sell for cash. She would teach, perhaps take charge of the school—a woman in the colony could raise a family and continue to teach, once each little one was beyond a few months of age. They would both write, not only for the Industrial Freedom, but for national publications such as the Coming Nation and Appeal to Reason. Together they might write a book about colony life; or perhaps a socialist novel. They might refurbish a beach cottage on Eliza Island.

The Industrial Freedom, the official newspaper for Equality Colony

published 1898 to 1902

from Wikipedia

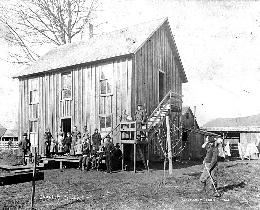

Apartment house at Equality Colony, ca. 1898.

courtesy Historylink.org

University of Washington Special Collections #UW1054 0

They were secretly engaged now, but as he was still a boy they would wait till his return to make it known. Then they would wait a proper number of months to be married. Secretly, Mike hoped that during the two year-plus hiatus she would convert to the Catholic faith. Though they weren’t discussing it now, he knew she wouldn’t object to their children being raised in the Church. Now the kisses they were sharing between happy banter were those of a couple with a planned life ahead—kisses playful, sometimes a bit passionate, but not lustful. By the time he let her off at Apt. House #1, a half-moon in the west gently illumed the contours of Colony Hill.

* * *

They sat in the back of a colony wagon as Harold Smithson drove. Up front with him, Mrs. Smithson mildly rebuked Anna’s giggling younger brother and sister as they took kitten-like swats at each other. The parents registered no displeasure at Mike and Anna holding hands while waiting at the crossroads for the Edison-Belfast stage, nor for the not-too-brief kiss their daughter gave him as he boarded the coach. Mrs. Smithson gave him a hug, followed by a hearty handshake and well-wishes from Mr. Smithson. Too soon Mike found himself curving up the hill at Brownsville, no one at his side, then over the flat summit through summer-dense woods and down the east slope, to catch the Great Northern train to Seattle. From there he would board the steamer Utopia for the inside passage trip to Skagway.