No, Tom Robbins, who died a year ago come February 9th, was not a friend. Or even a casual acquaintance. Though for a few years it seems like our paths crossed obliquely in the picture-perfect town of La Conner, Washington. And, truth to tell, even writing the above title is something of an embarrassment, as I much dislike “name dropping.” Especially as an unknown writer cozying up to an internationally known celebrity writer. Though we both have books for sale in the same waterfront bookstore in La Conner.

Tom lived in an unpretentious house on 2nd Street. For a time in the early 1980s, I lived on a tugboat at Pioneer Moorage, a motley collection of mostly wooden boats inhabited by a random element of fisherman, old-boat enthusiasts, would-be artists, maybe a poet or two–some with steady day jobs and some irregularly employed. And mostly survivors of the counter-culture years, with varying degrees of success. In short, a boiled-down version of La Conner’s historic roots as a produce marketing-and shipping-town transitioned into a colony of the artistic (such as Guy Anderson) and literarily inclined. And more recently and painfully, into a tourist destination.

Arching over the Swinomish Slough and Pioneer Moorage was the landmark Rainbow Bridge. The bridge is still there, but Pioneer’s ramp and floats and eclectic boats have long since vanished, some sunken and some surviving and scattered about, like their owners and inhabitants.

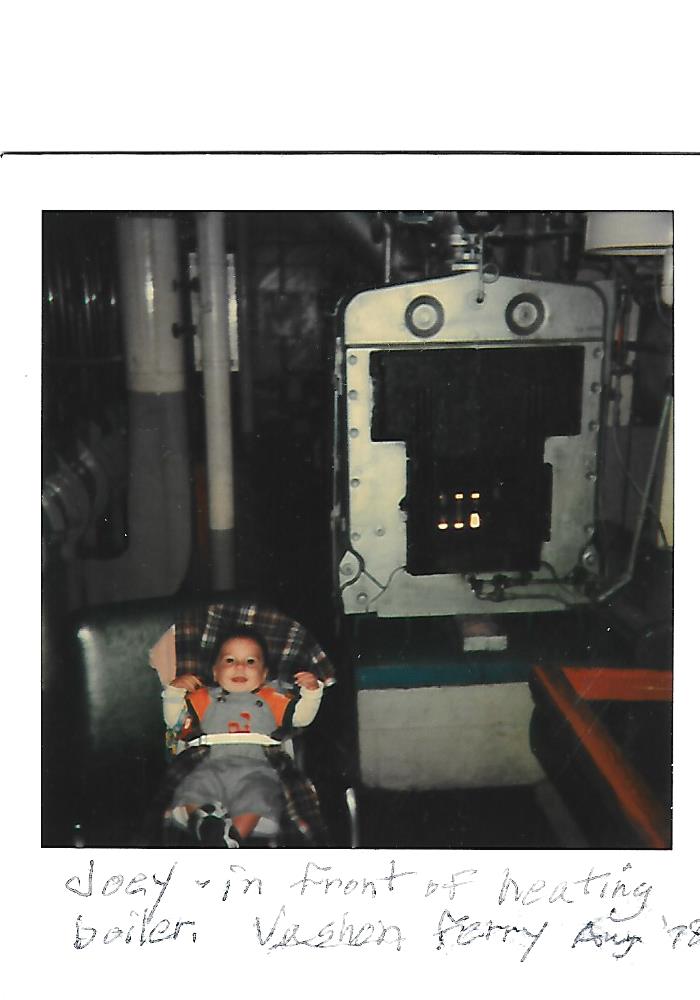

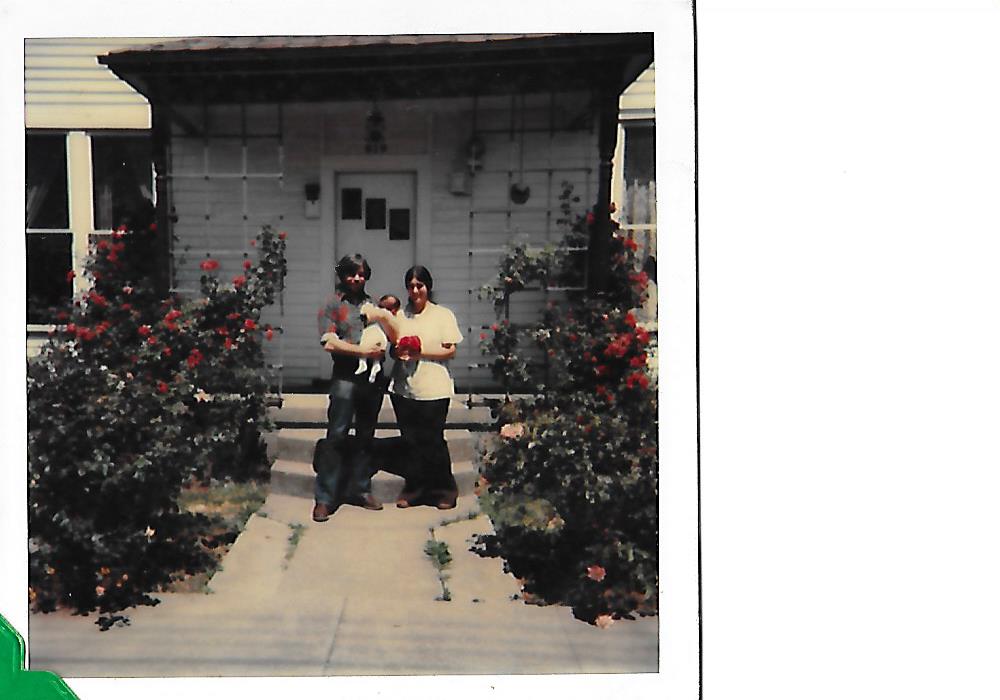

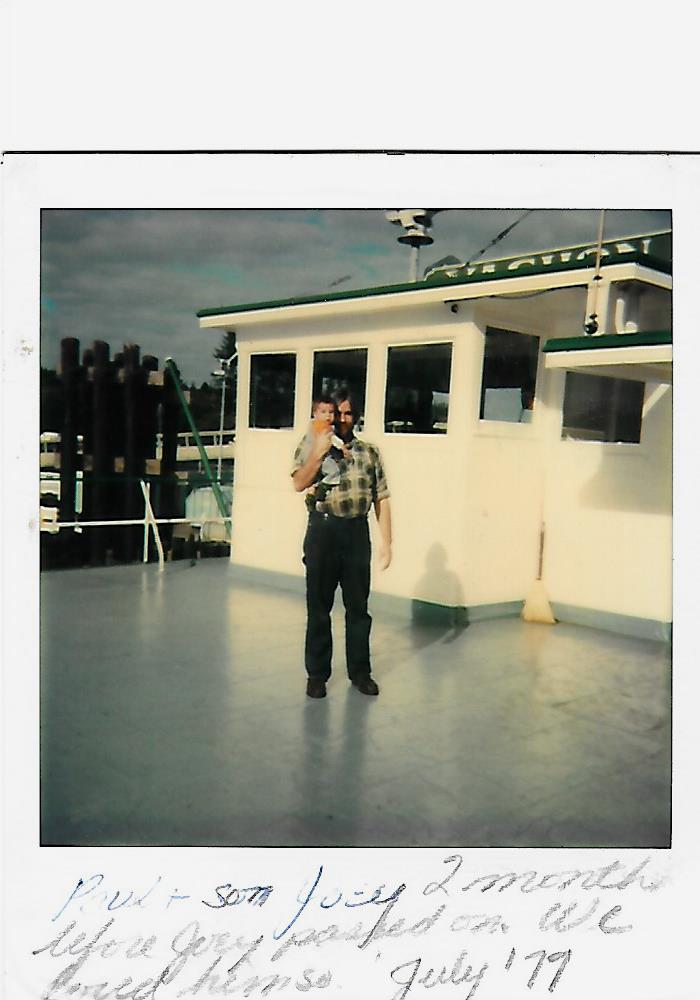

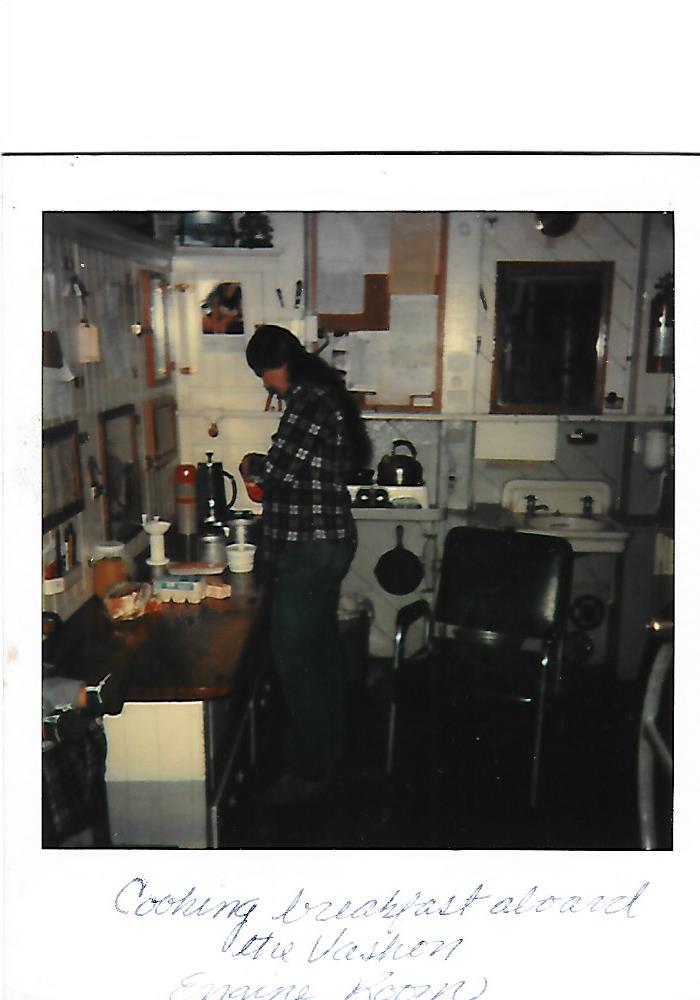

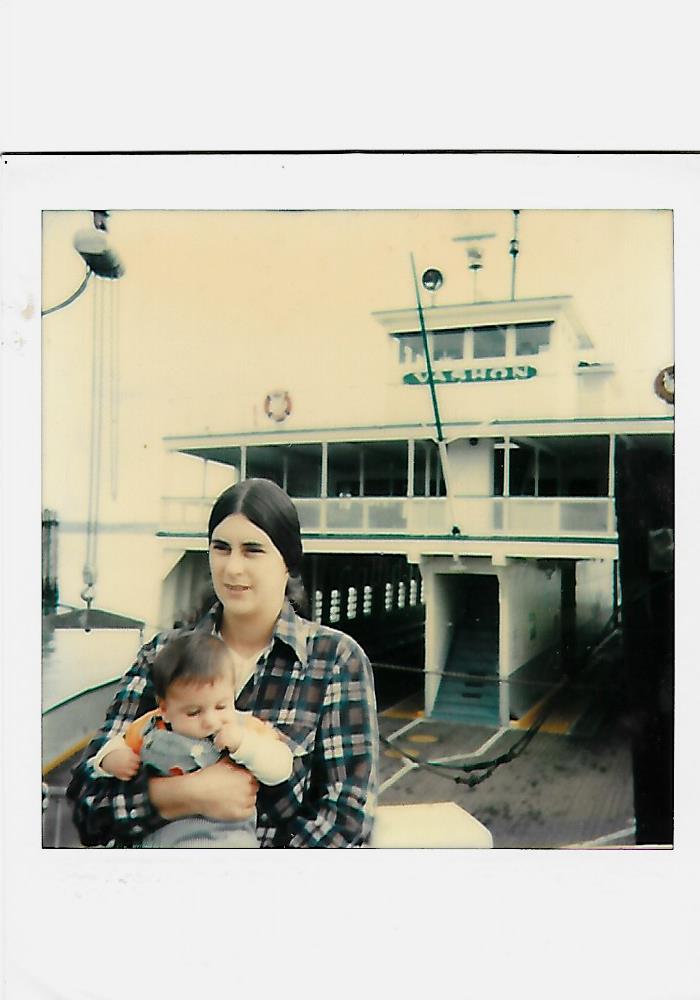

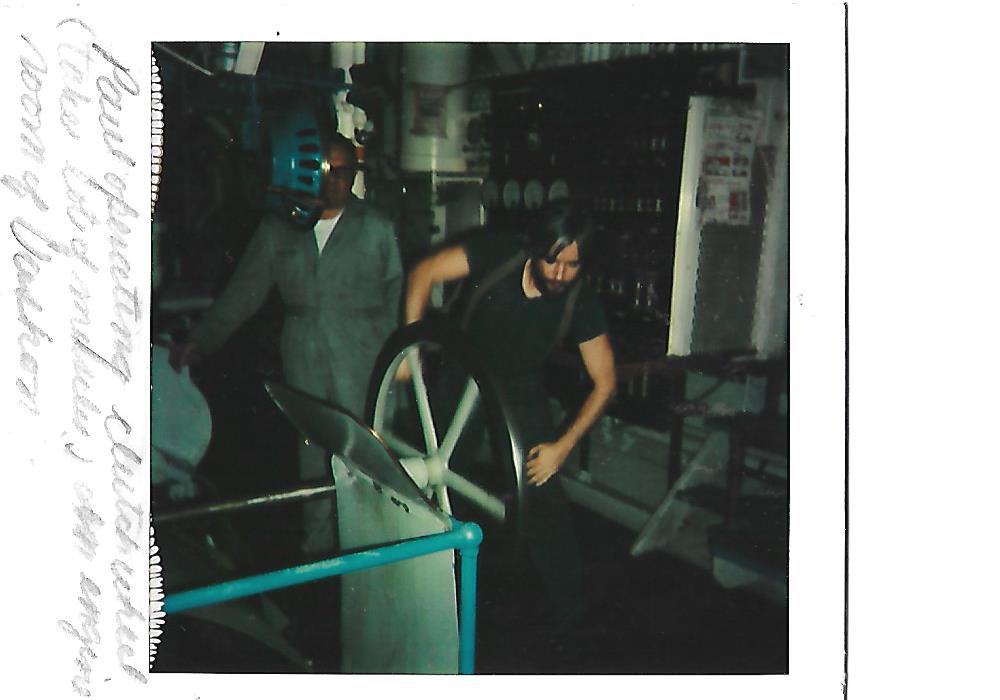

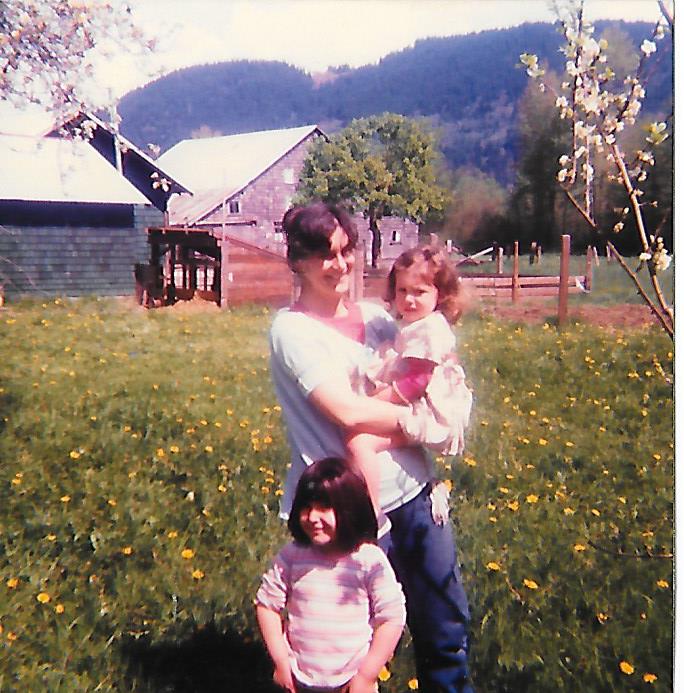

A mini-park is sited at where a shaky ramp once led to the floats and the boats. At the foot of the ramp was tied the largest boat there, the 74-foot Katahdin, built in the young Washington state in 1899 by Maine lumber interests. I’d been in the process of bringing back to life the long-neglected vessel on South Lake Union in Seattle, where it had worn out its welcome. And so I had it towed up to La Conner, where the unwelcomed and famed alike could find refuge. After our baby boy Joey died at age 7 months, I quit my job with the State Ferries. My wife Victoria and I sold our house in Anacortes and moved aboard the aged tugboat, with our year-old baby girl, Ellen Rose. A year later, another baby girl, Amy Jean, arrived. The Katahdin was now a floating family home, emitting enticing smells of home cooking and baking from the top-opened Dutch doors of the restored galley.

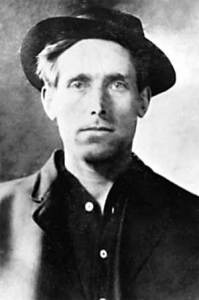

Bill Slater, with 5-year-old son Japhy, often tied up near us, motoring up on his gray double-ender with the add-on plywood shelter, to reprovision his cabin down on the Skagit Delta, where–likewise among poets and artists seeking refuge–he was neighbors with Robert Sund. Bill was known in the area for his wildlife paintings. He counted Tom Robbins among his closest friends, having known him since their days at the University of Virginia. The two had more-or-less come West together. I don’t know whether it was Bill or Tom who first came to La Conner, but Tom had been living in the house on 2nd Street, where Bill was a frequent visitor, since some time in the 70s.

I would pass by Tom or see him at the Post Office (Easily recognizable, he did, as he claimed, look like “Doris Day with a mustache”). I might end up with him in a checkout line at stores on 1st Street–places of business that didn’t survive the town’s makeover into a tourist destination. Such as Nelson Lumber, perhaps buying a stick of trim or a bag of nails. Or the La Conner Food Center, a very adequate grocery store housed in an un-historical Quonset Hut.

Tom moved comfortably among such settings, treated as any good customer. It was known that he liked a certain level of autonomy in his adopted hometown. It was only once I heard someone in a store blurt out, “Wow, are you Tom Bobbins? Far out!” Tom just nodded, with a slight–probably practiced–smile.

It was Donna who introduced me to him. I was delivering firewood (one of my side-gigs, to support my tugboat restoration habit) to her cozy little house on the north end. I’d first met Donna in 1978, when she lived with her son Jessie on a well-kept boat, an older cabin-cruiser dwarfed by the nearby Katahdin. Jessie was about the age of our son Joey, leading me to think they could grow up together and become best pals–which was not to be. So now, two years later, I was unloading firewood while making small talk with Tom Robbins in Donna’s backyard garden. I didn’t want to spoil this pleasant encounter by telling him my ultimate dream was to be a writer.

Donna and Tom were married that summer. Victoria and I received a wedding invitation, but for reasons that now escape me, we declined. Soon after getting our tugboat running under its own power, I sold the Katahdin to waterfront entrepreneur Peter Strong–who shared with me a fetish for historic old boats. But he normally didn’t let that cloud his astute business sense. Except perhaps for that one purchase. But he had the resources to complete the tugboat’s restoration. Not long afterward the Katahdin won first place in the retired-tugboat races up in Port Townsend. Around that time I bought a 1916-built 70-foot salmon tender, the Bofisco. My boats were getting smaller and newer. This one required a relatively small amount of work and actually paid its way as a workboat. For its first season, Bill Slater hired on as deckhand. I later lost track of Bill, who died in the 1990s. I recall reading his obituary written by Tom Robbins.

Tom Robbins’s first successful work, Another Roadside Attraction, was the first of his I read and has long been a favorite. And the only one that I’m aware of that actually took place in and around La Conner. I can still point out the building along Interstate-5 where the body of Jesus Christ was hidden and stored for a time. Though that plot twist might shock many, I recall no overt ridiculing of religion in Tom’s work. He did claim to be the grandson of two Southern Baptist preachers. If he had a message for readers of his own time, it was to “lighten up.” Admittedly a tough thing to do if one has the habit of reading the paper every morning. Which I do. But a message well worth a try, though yet more challenging if you’re a devotee of history.

The professional literary critics can decide if Tom Robbins’s playful narrative style was at least partly inspired by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Author of Sirens of Titan and Slaughterhouse Five, Vonnegut’s whimsy was darkened by his having witnessed the immediate aftermath of the fire-bombing of Dresden. Yet I found Vonnegut’s mixture of the light and dark strangely alluring.

I was also captivated by Wendell Berry and his social criticism. And Wallace Stegner and his steely yet panoramic realism. I didn’t quite to know what to make of Tom Robbins and his at-times cartoonish storytelling. And still don’t. But certain lines and phrases continue to do mischief in my mind, in a manner similar to that of the cow-flop mushrooms lurking in the soggy pastures of Tom’s (and my) adopted homeland of Northwest Washington: “A black candle at a wake for a snake;” “The sky was full of dead nuns.” And in a later work, his description of rap music: “Feeding a rhyming dictionary into a popcorn popper.” And after casting his narrational sandbags free from the rainy Northwest corner, a follower could float or soar into pyramid and flying-carpet territory; or witness the long-discredited god of nature, Pan, announcing his random reappearances with a musky smell and the tossing of beets; or indescribable highway travelers called Dirty Sock and Can of Beans; a road vehicle shaped like an Oscar Meyer hotdog; a girl with oversize thumbs who puts them to use as a hitchhiker and ends up at a cowgirls’ commune.

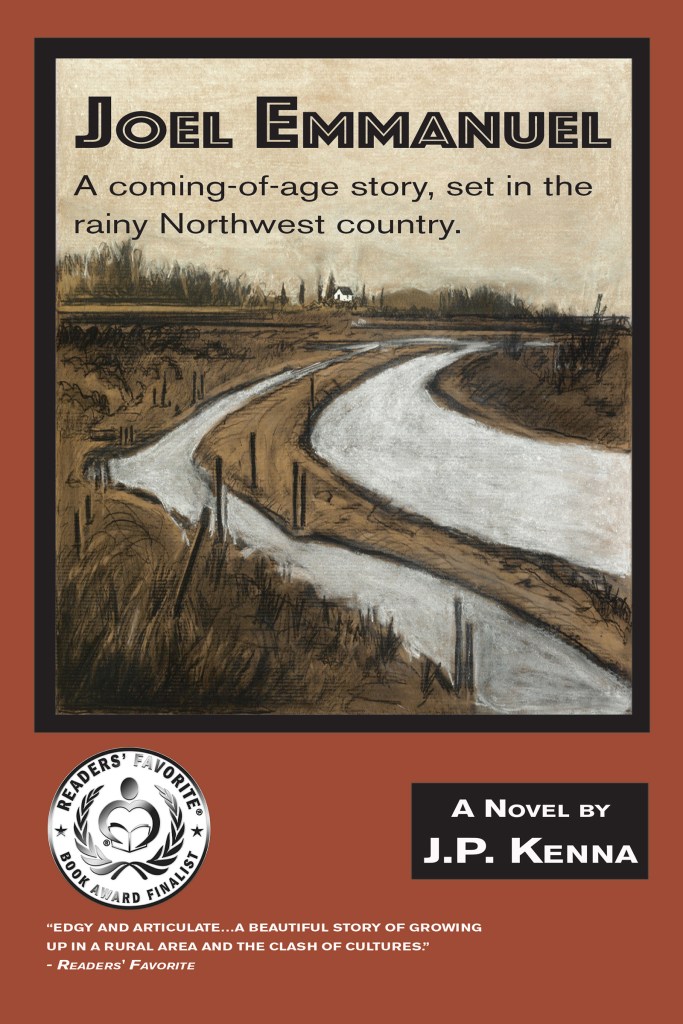

By the time I’d finished Joel Emmanuel in 2020, I had an idea about again meeting Tom Robbins. Like my favorite, Another Roadside Attraction, my novel tales place in and around 1970’s La Conner. I’d heard Tom was not totally opposed to people calling on him unannounced. So would I timidly knock on the front door of his approachable-looking house on 2nd Street and, if he answered, introduce myself, stating that we’d met in town over 40 years ago, that I’m sure he wouldn’t remember me, but there were people we knew in common, that I’ve written a novel taking place in La Conner, and that, well, other than certain locations, our stories really are quite different but, still, would he deign to read my book and, should he like it, write an endorsement? Would I address him as Mr. Robbins? Too pretentious. As Tom? Afterall, we’re both writers of fiction influenced by the counterculture. Both hippies at heart. But over 12 years apart in age, and he basking for 50 years in celebrity-author fame, And I, a supplicant. Having been in difficult introductions and situations before, I’m not one to stammer and shuffle my feet. Could old-fashioned Irish Blarney see me through? I could maybe give a little laugh and say, “You know, Tom, I’m as of this moment starting to see myself acting in a really cheesy novel. Sorry to drag you into it!” Would that break the log jam? If he answered with a smile of his own, I might mention that we both have books for sale down the hill at Seaport Books. “Small world, isn’t it, Tom?”

Well, as we know, Tom Robbines died early this passing year. That imagined encounter was not to come about.

If you’re not already famous, writing a book is all about supplication. “Please buy my book!” Or better, enticement. Visit the picture-perfect historic town of La Conner, decorated for the Christmas season. And while there, visit a cozy picture-perfect little bookstore on the waterfront, Seaport Books. Browse leisurely or chat with the friendly staff. Pick out a few books to give as heartfelt gifts , or for your own reading pleasure. And may I suggest two authors who lived in La Conner and made as a setting this most beautiful and unique corner of these United States? One needs no introduction. Below is another:

Distance a factor? “Hook a book” at Seaportbooks.com.

With grateful thanks to:

Alex

Tricia

Marion

Jana

May your efforts at Seaport Books continue to help make this most beautiful corner of the world so extraordinary. -J.P. Kenna