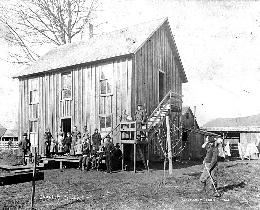

34-year-old Mike Scanlon, itinerant worker and I.W.W. member–along with some 40 others–has managed to survive a beating the previous Monday night at Beverly Park, south of Everett. Led by the Snohomish County Sheriff, the attackers were made up of several hundred recently sworn-in “deputies,” many associated with the Everett Commercial Club. Mike writes of the event–which left many of his cohorts hospitalized–to his father back in Riverport, New Jersey.

34-year-old Mike Scanlon, itinerant worker and I.W.W. member–along with some 40 others–has managed to survive a beating the previous Monday night at Beverly Park, south of Everett. Led by the Snohomish County Sheriff, the attackers were made up of several hundred recently sworn-in “deputies,” many associated with the Everett Commercial Club. Mike writes of the event–which left many of his cohorts hospitalized–to his father back in Riverport, New Jersey.

Excerpted from the manuscript of The Dark And Strange Flow, by J.P. Kenna (not yet published). Historical Fiction with an Irish-American slant.

Seattle, Wash.

Nov. 4, 1916

Dear Dad,

Thank you for your last letter. I realize now that election day is just a few days away and I’ve barely been thinking about it. I suppose I shall cast a vote for Wilson, what with Debs not running. Yet I’m unable to forget how one year minus two weeks ago—following a halfhearted intervention—Wilson allowed the State of Utah to execute Joe Hill by firing squad; illustrating exactly, I think, where the Democrats really stand on the plutocrats’ war on workers—as the firing squads in Dublin the following May illustrate the true English feeling for the Irish.

But speaking of the war on workers, this past Monday night a bunch of us got roughed up a bit outside of Everett. Other than some aches and bruises, and a couple of stitches over my right eye, I’m okay. There were over 40 of us and many had to go to the hospital. Dad, you wouldn’t believe what the forces of “law and order”—at the behest of the Lumber Trust—are doing in Everett, Washington. The group of us who arrived there that evening was twice as large an any that have tried to break the city’s illegal blockade. And tomorrow a group that could number in the hundreds is going to try to do the same. I’m sure you’ll be relieved to know I’ve made the decision to not be part of tomorrow’s effort—the culmination of a week long campaign by the Seattle I.W.W. office, telegraphing out notices throughout the region in what is being billed as the biggest Wobbly event since the Spokane free speech fight of ’09.

My friend Marty O’Grady, in writing for the Industrial Worker, states that “the entire history of the organization will be decided at Everett.” That’s after emphasizing that it is the “sheriff and his vigilantes” who are advocating violence—while the I.W.W.s are planning a peaceful assembly in that city, to give speeches and allow themselves to be jailed. He further writes:

Workers of America, if the boss-ruled gang of Everett is allowed to crush Free Speech and organization, then the Iron Hand will descend upon us from all over the country. Will you allow this? It is for you to choose! Every workingman should help in every way to put an end to this infamous reign of terror. ACT NOW!!!

He makes a good case and the men and boys are responding. As we descended on Spokane exactly seven years ago, the loggers, field hands, laborers, carpenters, painters, railroaders, seafarers, miners, printers, etc. have been all week arriving in Seattle, by boat, by passenger train, by “side door Pullman.” Many of them were young kids in 1909 and for them the Spokane fight has taken on a legendary status. Men my age and beyond, who were there, are looked upon as “old heads.”

My decision to not accompany them to Everett tomorrow was made after soul-searching and a little praying. Some of the men going there were busted-up at last Monday night’s beating but are no longer confined to hospital beds. I suspect vengeance may be in the back of some their minds, but mostly they want to inform the citizenry of just what mill owners such as David Clough and Roland Hartley—backed by bankers such as William Butler—are allowing, even encouraging, to happen. I know reprisal has been on my mind, which is one of the reasons I’m not going. (I’ve prayed for God to erase notions of vengeance from my heart—not something I can do on my own.)

I shall spare you, Dad, descriptions of the “event” that happened outside of Everett last Monday night—from which I emerged less stove-in than many—but will here give you a summary of its aftermath. Early Tuesday morning a few of Sheriff McRae’s deputy-goons returned to the scene of the night before, where they met with the Ketchum brothers. These two men had heard the ruckus from their farmhouse a quarter-mile away. From them the deputies learned no bodies were found—relieving these forces of law and order of fear that they could be charged with murder. They then made an attempt to clean up the scene of their drunken bloodlust.

Apparently they didn’t do a very good job. Soon after they’d returned to town, an impromptu committee went out to examine the site. Led by Ernest P. Marsh, President of the Washington Federation of Labor, the group included two well-respected ministers—one from Seattle, one from Everett—along with Jake Michel of the Trades Council, Snohomish County Prosecutor William Faussett, Commissioner W.H. Clay, and other prominent Everett citizens. Mr. Marsh reported:

“Hearing of the occurrence I accompanied several gentlemen, including a prominent minister of the gospel in Everett, next morning to the scene. The tale of that struggle was plainly written. The roadway was stained with blood. The blades of the cattle guard were so stained, and between the blades was a fresh imprint of a shoe where plainly one man in his hurry to escape the shower of blows, missed his footing in the dark and went down between the blades. Early that morning workmen going into the city to work, picked up three hats from the ground, still damp with blood. There can be no excuse for nor extenuation of such an inhuman method of punishment.”

A Mr. J.M. Norland, part of Marsh’s committee, states:

“There were big brown blotches on the pavement which we took to be blood. They were perhaps two feet in diameter, and there were a number of smaller blotches for a distance of 25 feet. In the vicinity of the cattle guard the soil was disarranged. Some of these were shoe marks. …You could also notice where, in their hurry to get across, they would go in between, and there would be little parts or shreds of clothing there, and on one there was a little hair.”

Returning to town, Mr. Marsh and his committee proposed a mass meeting—such as was held Sept. 20—to inform the people of Everett exactly what their county sheriff and his Commercial Club “citizens’ army” had done at the crossing near Beverly Park. No word of the Monday night occurrence appeared in the following day’s Everett Herald or Tribune. Marsh suggested the coming Sunday, Nov. 5 (which is tomorrow), as a day for a general citizens’ meeting. In an effort to inform all involved parties, he notified our Seattle I.W.W. office. Whereupon our local, as I mentioned, decided to “shirttail” a free speech demonstration onto Marsh’s proposed meeting. Certainly I have no objection to a Spokane-style free speech event. But it should not upstage a citizens’ meeting—hosted by Everett’s most respected labor leaders, ministers and other prominent citizens—whose purpose is to further expose, and hopefully disgrace, McRae and the Commercial Club. This, it would seem, would most benefit the striking shingle weavers, whose plight inspired I.W.W. intervention in the first place.

In any event, by the time you get this letter, Dad, Sunday the 5th of November will have come and gone and you’ll be able to read about it in the Industrial Worker and Solidarity—though likely not in the big dailies, not so long as there is war news to report from France. Along with a presidential election.

I need to go to bed now. I know you’ll say nothing to Mother about any of this. But I’m still sore from a few glancing pick-handle blows inflicted last Monday. But luckily nothing hit so as to worsen my previous injuries. And unlike a goodly number, I didn’t end up in the hospital. Which is what I fear may happen to quite a few more tomorrow.

Goodnight, Dad

Your longtime wayward son,

Mike

To be Continued.