“Those in power write the history, while those who suffer write the songs, and, given our history, we have an awful lot of songs.”

–Irish balladeer Frank Harte

Tuesday, May 2, 1916

When informed of the shooting of “Skeffy” Skeffington—and other civilians playing no direct part in the rebellion—by the pitiless Captain Bowen-Colthurst, Secretary of War, General Lord Kitchner expressed outrage that such atrocities could occur in the British Army. Major Vane left with a telegram ordering that Bowen-Colthurst be arrested and face court martial.

Secretary of Ireland Augustine Birrell crossed the Irish Sea enroute to London, to formally tender his resignation to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

That afternoon in Dublin, Thomas Clarke, Patrick Pearce and Thomas MacDonagh were taken to Richmond Barracks for court martial—a General Blackadder the presiding military judge. Old Tom Clarke, dressed in an undertaker-like black suit, stood unmoving before the tribunal, refusing to enter a guilty or not-guilty plea. Pronounced guilty, he was led away in head-held-high silence. Next came Patrick Pearse. In contrast to the wordless Clarke, he gave a speech, its opening paragraph reaching back to the eloquence of John Mitchel and Wolf Tone.

“From my earliest days I have regarded the connection between Ireland and Great Britain as the curse of the Irish nation, and felt convinced that while it lasted, this country could never be free or happy.

“When I was a child of ten I went down on my bare knees by my bedside one night and promised God that I should devote my life to an effort to free my country.

“I have kept that promise.

“We seem to have lost. We have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose; to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past, and handed on a tradition to the future.

“I repudiate the assertion that I sought to aid and abet England’s enemy. Germany is no more enemy to me than England is. My aim was to win Irish freedom; we struck the first blow ourselves but should have been glad of an ally’s aid.

“I assume that I am speaking to Englishmen who value their freedom and who profess to be fighting for the freedom of Belgium and Serbia.

“Believe that we, too, love freedom and desire it. To us it is more desirable than anything in the world. If you strike us down now, we shall rise again and renew the fight.

“You cannot conquer Ireland. You cannot extinguish the Irish passion for freedom. If our deed has not been sufficient to win freedom, then our children will win it by a better deed.”

Observers say General Blackadder stared at him transfixed.

The military judges pronounced both Pearse and MacDonagh—both published poets, and teachers at St. Enda’s—guilty.

John Dillon, of the Irish Nationalist Party in the House of Commons, visited General John “Conky” Maxwell, warning him that executing the rebel leaders will send them to immortality and that, more immediately, will turn the people against the English—who thus far have opposed the rebellion and supported its suppression. Maxwell listened impatiently, then replied that when he was finished, there would be no treason even whispered in Ireland for the next 100 years.

That same afternoon, Joseph M. Plunkett, pale and tubercular, was called into court martial and pronounced guilty. He took hope in a rumor that the prisoners were to be sent to England, that he might yet marry Grace Gifford—their Easter wedding now postponed for over a week—by proxy.

In New York, John Devoy read through the papers. The New York Times pronounced Roger Casement “treacherous and perfidious.” Not really true, Devoy thought. More like addled and incompetent. The Washington Post suggested Casement be imprisoned and forgotten, that executing him in the Tower would make him an undeserving martyr. The Philadelphia Enquirer called for life imprisonment. Other papers stated the uprising was counterproductive to Irish freedom. Whoresons! Devoy whispered to himself, before putting a phone call through to McGarrity in Philadelphia.

Late afternoon in Dublin, Clarke, Pearse and MacDonagh were informed they would be shot at sunrise the following day. Forthwith, they were led away to the gothically grim Kilmainham Jail.

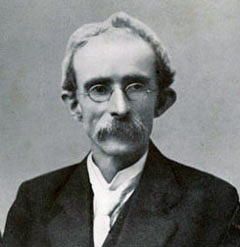

To Tom Clarke, being shot was the preferred alternative to returning to yet more years in prison. He’d been freed 18 years before, prematurely aged at 41 years old, having gone in as a youth of 21. In his solitary cell that night, he must have thought of his time in Portland Jail, locked up for 11 years near John Daly, his future wife’s uncle—where one of his better memories was providing flies for the spiders Daly kept. Both in solitude, the men had communicated by tapping on stone.

Pearse considered it an honor that he would spend his last night alive in Kilmainham, the Bastille of Ireland. It had housed Napper Tandy in 1798; then early in the next century, Robert Emmet, in prelude to hanging followed by beheading at age 25; and John O’Leary, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, and Charles Stewart Parnell; and John Devoy (who later exiled himself to New York, to print the Gaelic American).

That same afternoon, unbeknownst to Pearse, Joe Plunkett, Michael O’Hanrahan and Ned Daly—Tom Clarke’s brother-in-law—were court-martialed.

That night, General Blackadder dined as a guest of the Countess of Fingall. To those at the table, he announced he had just condemned to death one of the finest characters he’d ever happened upon—a man by the name of Pearse. Between sips of wine, he commented sadly on the state of society, that a poet and teacher—said to be adored by his pupils—should become a rebel.

In the night Kathleen Daly Clarke, pregnant with their fourth child, was allowed to visit her husband—following a visit by the young Capuchin friar, Father Columbus, from whom Old Tom refused the sacraments.

Pearse had a more satisfying visit from young Father Aloysius—who then went on to administer to MacDonagh, who asked if he could have his sister—a nun in a nearby convent—visit. Father Augustine arranged with the British major in charge to have Sister Francesca brought over in an automobile. After receiving Communion, Thomas MacDonagh gave to Father Aloysius a picture of his very-young children, Donagh and Barbara. These he entrusted with the priest to be delivered to wife Muriel (sister of Grace Gifford, betrothed to Joe Plunkett), along with a farewell note to all three of his family.

Wednesday, May 3, 1916

In the early hours, Sister Francesca was told the time visiting her brother in the tomb-like cell was over. “The national rose of Ireland is An Roisin Dubh, the Little Black Rose, not the tender red flower to be plucked with the joys of life,” she remembered her brother once saying. Now giving him their mother’s rosary beads, she asked him to wear them, that he might be embraced by them in his final moments. Tom MacDonagh informed his sister the beads would be shot to bits.

First to be led at dawn into the Stonebreakers’ Yard—the site of centuries of penal labor—was Old Tom Clarke. The procedure for MacDonagh and Pearse would be the same; blindfolding, a paper heart pinned to the left side of his chest as target, a 12-man firing squad—six kneeling, six standing—pulling triggers on order, then with the victim lying in quivering death throes as the blood pooled over the stones, a final pistol shot to the head by the presiding officer.

The gun shots were heard by all in the moss-dripping stone cells of Kilmainham, including Pat Pearse’s brother Willie. As the bodies were hauled on truck-bed through the streets of Dublin under the darkness-chasing gray light of emerging day, on the way to General Maxwell’s quicklime pit, Father Aloysius—in black vestments—was saying a Requiem Mass.

“A shame,” an Irish guard—who’d heard of the quicklime pit—was heard to say. “Not even their guardian angels will recognize them.”

Returning to pick up Pearse’s crucifix and MacDonagh’s damaged but still-intact rosary beads, Father Aloysius appealed to the major in charge that in the event of more executions, he be allowed to be with the men as they were fallen, that a man being executed cannot receive the Last Rights anointment until just after the moment of death. “Just before the soul leaves the body,” the kindly young bearded friar clarified. The commandant—sympathetic, though puzzled by the Irish and their obsessively-ritualized Catholic ways—agreed to the request. The priest then steeled himself for the task of visiting the now-fatherless MacDonagh family, and to Pearse’s elderly widowed mother, who still had one surviving son.

Surely, Father Aloysius thought, they would spare Willie—still a boy at heart, who idolized his brother, but had no real role in planning or leading the Rising.

Prime Minister Herbert Asquith expressed concern at the shooting of so many rebel leaders—though thus far there were only three—and requested that the Countess Markievicz not be executed.

At 3 p.m. Augustine Birrell announced his resignation to the saddened Prime Minister. Sir John Redmond, parliamentry chairman of the Irish Nationlists—an Irishman who got on with the English—and Augustine Birrell—an Englishman who loved Ireland—each faced a very unsympathetic House of Commons to deliver their “swan song” speeches. With none of his characteristic wit and grace, looking yet more rumpled than usual, Birrell made a perfect target for heckling. And Redmond too was witnessing his own political death, ruminating on the fact that were not his approved Home Rule bill shelved—thanks to the war with Germany and the efforts of Edward Carson—there would have been no rebellion and he would have been elevated to Head of the Irish Administration.

At 11:30 at night, Joseph Mary Plunkett and Grace Gifford were married in the forbiddingly ancient and austere chapel at Kilmainham Jail—Father Eugene McCarthy, jail chaplain—presiding. Two soldiers were pressed into service as witnesses. At the end of what must rank as one of history’s most joyless weddings, Plunkett—29 years old and still short of his full flowering as a poet, facing death by both disease and, more immediately, by tribunal—was led back to his cell.

Reference: Rebels, by Peter De Rosa

This breaks my heart but is beautifully written. The words of the poet will stay in my heart forever.

Thank you. The whole Easter Rising is a hear-wrenching footnote to World War One–itself a tragedy on a yet more horrific scale.

A fine rendering of tragic events in recent history. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you. I’m looking forward to more of your posts.

Pingback: How the recent presidential election reflects a shift from Ireland’s Catholic founding fathers - EWTN Ireland - Catholic Television for Ireland

Pingback: How the recent presidential election reflects a shift from Ireland’s Catholic founding fathers — By: Catholic News Agency – Saint Elias Media

Pingback: How the recent presidential election reflects a shift from Ireland’s Catholic founding fathers - Catholic Telegraph

Pingback: How the recent presidential election reflects a shift from Ireland’s Catholic founding fathers

Pingback: How Recent Presidential Election Reflects Shift From Ireland’s Catholic Founding Fathers – Analysis – Yerepouni Daily News