Gaining fame for ensuring the safety of President Lincoln on his inaugural trip to Washington D.C. back in 1861, by the 1890s The Pinkerton Detective Agency had evolved into a multifaceted organization chiefly known–and despised among the laboring classes–for providing armies of strikebreakers (“scabs”) during labor disputes, often hiring thugs off the streets.

July 6, 1892: At dawn, a first attempt to file ashore from the barges and take possession of Andrew Carnegie’s Homestead Steel Works began.

Excerpted from Chapter 21, Beyond the Divide–Available from Village Books, Fairhaven (Wash., U.S.A.); and from Amazon

As the hired agents in the barges slowly emerged on deck, the clearing dawn revealed to them an unexpected sight — throngs of townspeople on shore outnumbering them ten-to-one, brandishing weapons from clubs to Civil War muskets to high-powered rifles. The gangplank was lowered.

A lead group of Homestead defenders, the high-strung William Fay in front, followed by five more including Anthony Saulier, William Murray and Joseph Sotak — leader of the many East European immigrant steelworkers — advanced toward the first barge. As they moved with weapons cocked, Fay lay down prone at the foot of the gangplank.

In the inevitable confusion, two shots sounded, the first wounding Fay, the second Capt. Heinde. A battle raged for ten minutes, killing one Pinkerton and several Homesteaders, including Sotak, and wounding scores on both sides. O’Donnell, aided by Homestead burgess John McLuckie, attempted to keep order, as a lull set in and the sun rose and the fog lifted. Across the shore, the local Grand Army of the Republic veterans’ post had set up a 20-pound-cannon, trained on the barges.

A second attempt to disembark followed at 8 a.m. More shooting followed and four more Homestead workers fell.

Meanwhile, the tugboat Little Bill had departed, leaving the barges stranded. Trapped inside, many of the Pinkertons refused to fire. Some hid as best they could. When the G.A.R. cannon from across the river began to fire, total panic set in. Close to 11 a.m. the Little Bill returned in an attempt to rescue the barges but was repulsed by shore-side fire, leaving the Pinkertons again stranded.

Next the Homesteaders sent a raft of burning oil barrels floating toward one of the barges, intending to set it afire. Soon, a railroad flatcar — similarly loaded and blazing — careened down the tracks out onto the wharf, at the end of which sat the barges. The raft failed to set the large-timbered barge ablaze and the flatcar rolled to a stop before reaching the end, the attempts succeeding only in further increasing terror among the hapless agents. As the shots continued, another Pinkerton fell, Thomas J. Connors, shot while cowering under improvised cover. His agonizing death-bleed led to the raising of a white flag from the barge, only to be immediately shot down.

To observers, it appeared the Pinkertons were being sacrificed by Henry Clay Frick to justify calling out the Pennsylvania State Militia. No help was seen coming from the Allegheny County Sheriff’s department. By 4 p.m., with reports that Sheriff McCleary was planning a rescue of the Pinkertons, 5,000 men from neighboring mill towns had filtered in to reinforce the Homesteaders. Telegrams of support and congratulations poured in from labor organizations throughout the nation. Meantime, a contingent of national labor leaders, who had arrived at Homestead to persuade the workers to peacefully allow McCleary and his deputies to remove the Pinkertons, were ignored or shouted down.

By 5 p.m. another white flag arose from the barge Iron Mountain, following another attempt to set it afire and the blowing off of a few dynamite sticks — again causing more terror than real damage. O’Donnell and the Workers’ Advisory Committee had meanwhile come to an agreement with their fellow mill workers to accept surrender by the Pinkertons and hold them until they could officially be arrested on murder charges.

When the Pinkerton agents, now prisoners of the citizens of Homestead, were led off the barges, they were made to pass through a “gauntlet” along the beach, made up of Homestead citizens on either side in a line 600 yards long. According to a Pittsburgh Press reporter:

As the Pinkertons neared the top of the bank, they were helped along with kicks and cuffs. One man received a slap from a woman and attempted to strike back. He was at once hit on the head with a stick and blood flowed freely. Other women punched the fellows in the ribs and belabored them with switches. The Pinkertons followed each other closely. Many of them were bare-headed, others well-dressed, but most of them were tough-looking. No mercy was shown them .… The men … were punched by every man that could get a lick at them. The Hungarians were particularly vicious and belted the men right and left. They were knocked on the head and struck in the face. The men plunged wildly onward, begging for the mercy which they received not. No distinction was made. They were hit on the heads with hand-billies and clubs and sticks and stricken to the ground. Onward they plunged, bleeding and dazed.

The sorry procession continued toward the mill. Hugh O’Donnell and some of the other Advisory Committee men made efforts to restrain their neighbors and fellow workers. Women and boys stormed the now-emptied barges and, stripping them of all useful domestic objects, set the vessels afire.

Continued the Press:

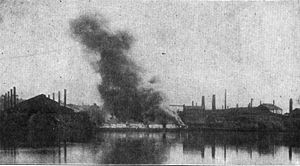

The delight of the onlookers at this finale to the tragic events of the day knew no bounds. They cheered, clapped their hands and even danced with glee while the dry wood blazed and crackled, and two huge columns of smoke rose lazily toward the sky and formed clouds overhead. Not until the vessels had burned to the surface of the water and the last hissing embers disappeared beneath the placid bosom of the Monongahela did the enthusiasm abate.

As the men were paraded through the mill, crowds of mainly women and children formed at the entrance.

Many women and children in one confused mass surged rapidly toward the works. Many young women who were mild and gentle-looking stood in their gateways and cried to the men as they rushed by: “Give it to the blacksheep*, kill them all!”

Added a reporter from the New York Herald:

Well-bred and well-dressed women stood on front steps and laughed aloud at the sight of the miserable creatures staggering along the sod. … The thirst for blood had possessed these women, too, as surely as it ever did the Roman maids and matrons of the Coliseum, as there they stood in their doorways and laughed at sights which on any other day they would have fainted.

Near the Homestead Opera House, suitcases were snatched from a few of the agents who still kept any belongings and were thrown open as personal items, including underwear, were tossed in the air.

John McLuckie and Hugh O’Donnell managed to bring a semblance of order by 6:15 p.m., by which time the prisoners were secured to await the official train on which Sheriff McCleary would be aboard to arrest the Pinkertons on charges of murder and return with them to Pittsburgh, to the Alleghany County Jail. According to the New York Herald, by 11 p.m. in Homestead, the steelworkers were “jubilant over this official action,” which “places law on their side.”

*an epithet for scabs–strikebreakers

_______________________

It’s rare for the law to be on the side of wage-earners, Jimmy thought, putting the newspaper pages aside. He’d long ago learned from his father and Daniel Quinn that the established papers usually got the gist of the story correct but often misstated or confused facts, and that a certain amount of lurid prose was needed to make the newspapers sellable and this in turn created competition among reporters to produce the most sensational versions. But he also had seen enough of human nature to know that normally-decent people could be reduced to savage actions, sometimes for understandable reasons.

To be continued