Our son, Joseph Patrick Kenna, would’ve been 43 years old tomorrow, April 3rd.

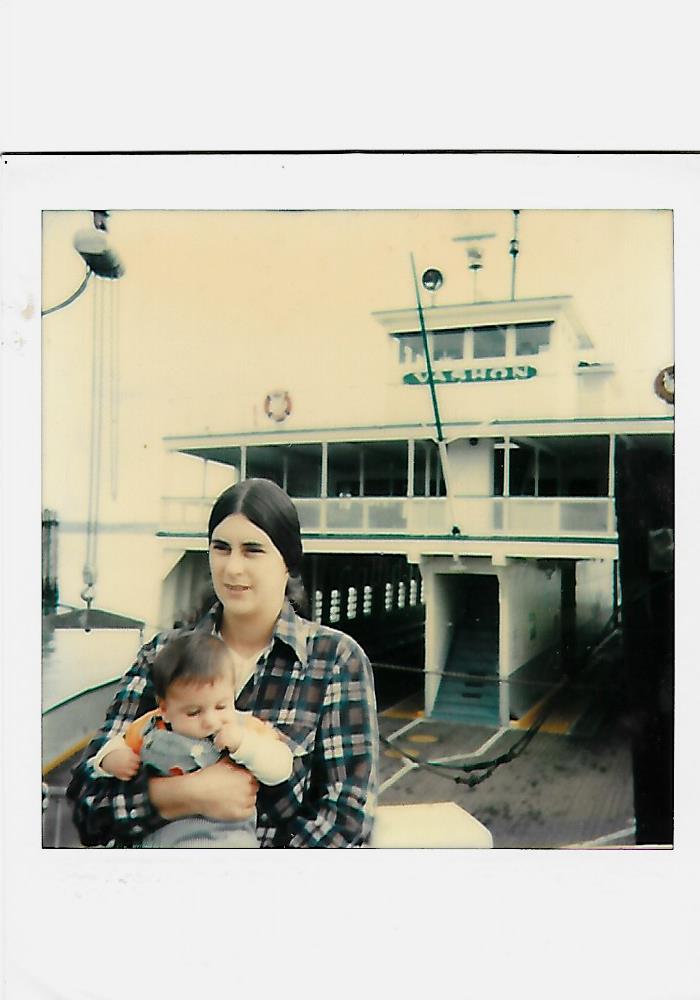

In summer of 1978, my wife, Victoria, and I bought a house in the Puget Sound waterfront town of Anacortes. We were 33 years old. I’d been working for a little over a year as an engine-room oiler for the Washington State Ferries, and was now happily assigned to a boat I loved, the 1930-built Motor Ferry Vashon. Though not the oldest boat in the ferry fleet, she was the last remaining wooden vessel, with the added distinction of being the least-modified .

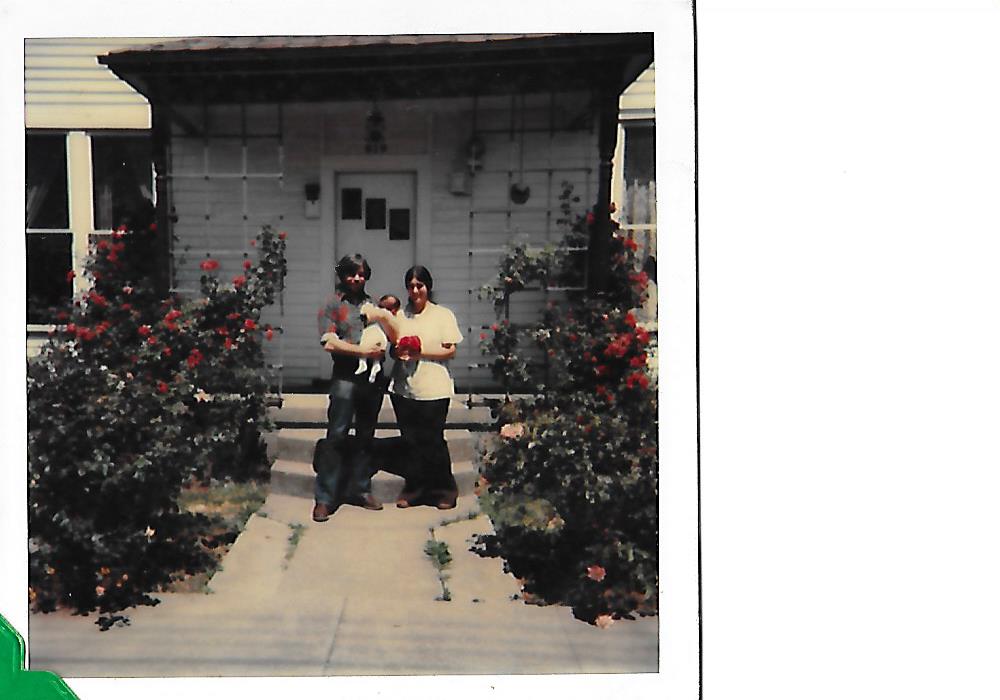

Victoria contentedly divided her time as new mother and homemaker in our 1890’s-built “city farmhouse” (with a 1950’s front door), and teaching Spanish evenings at the Fishermen’s World Market. It had been three years since the loss of our first child; a full-term baby boy delivered stillborn, who looked like a sleeping angel.

We were now a complete family, with a live and lively baby boy, inhabiting a home of our own. The house sat in a residential block near the old Anacortes city center. The small front porch sat amidst summer-blooming rose bushes. The backyard was roomy enough for a generous garden and featured a grape arbor of dense vines drooping from an old swing set. Between it and the garden site were three green-gage plum trees.

The front looked out over the boat harbor and Samish Bay, and in the distance, the Shell and Texaco oil refineries–incongruous in the idyllic setting of treed islands and distant mountains–though for me, a native of northeastern New Jersey, the sometimes smoky industry had an air of familiarity. Victoria, a native of Seattle 80 miles to the south, was eager to pursue her dream of starting a food co-op in our newly-adopted smaller city.

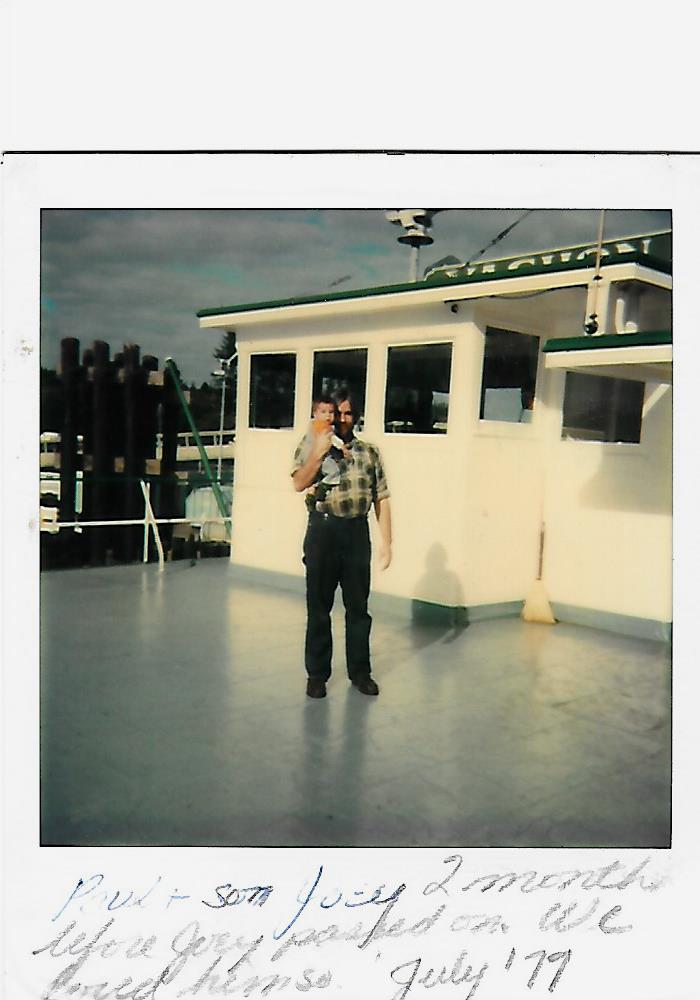

Contentment can carry mixed messages; such as fear that it might be an illusion. The tragedy of the stillbirth, three short years in the past, had thrown our lives, our marriage, into disarray. We pulled through, and now were reaping what seemed like manna from heaven. We want more from shared lives than to star in its tragedies. To be the father of a living boy was a new experience. Alert, handsome and in fine health, one could only look into his future with optimism. He might follow his father into marine engineering. Or his grandfather Leonard into a railroad career. Or grandfather Joseph into accounting and later banking. Or into teaching or law or politics. Or into occupations at the time unforeseen and unknown. In any direction, I could see only success.

Entering middle age had been a double-edged sword. Now I felt not only justified, but in a sense larger. I was ready to strut a bit. I had a union job that, though far from perfect, paid what’s now called a “living wage.” My family would be protected by a good healthcare plan. In less than two years I could take the exam for First Assistant Engineer. In three years I might qualify as a Chief Engineer. But such a position could necessitate leaving the boat I’d loved at first sight. The Vashon was a working boat that also could qualify as a “museum piece.” Long before it became a fashionable term, she’d been “locally sourced.” Built on Lake Washington in 1930, her hull and superstructure were of stout Douglas fir. Her main and auxiliary engines and all electrical equipment were original, from Seattle’s Washington Iron Works. The riverboat-sized steering wheels (one on each end), with manila rope and steel cable mechanism, were–like everything on the boat–“low tech”, long-lasting and dependable. With the possible exception of the radar sets, one in each wheel house–along with radios and depth sounders–the vessel was devoid of “modern” appurtenances. And none graced the engine room.

The Vashon ran out of the San Juan Island ferry terminal west of Anacortes, serving as a summer-only boat connecting the islands Lopez, Shaw, Orcas and San Juan. On her “deadheading” runs between the Anacortes terminal and first stop at Lopez Island, she carried no passengers or cars. Fares came from local islanders, riding from one island to another in the San Juan chain. During County Fair season in August, the bleating of sheep or goats or mooing of cows could be heard above on the main deck, coming from trailers or small livestock trucks, bound for the fair at Friday Harbor, on the “main” island.

Connecting the islands to the mainland were the jobs of more modern (and at times less dependable) boats of the extensive ferry system.

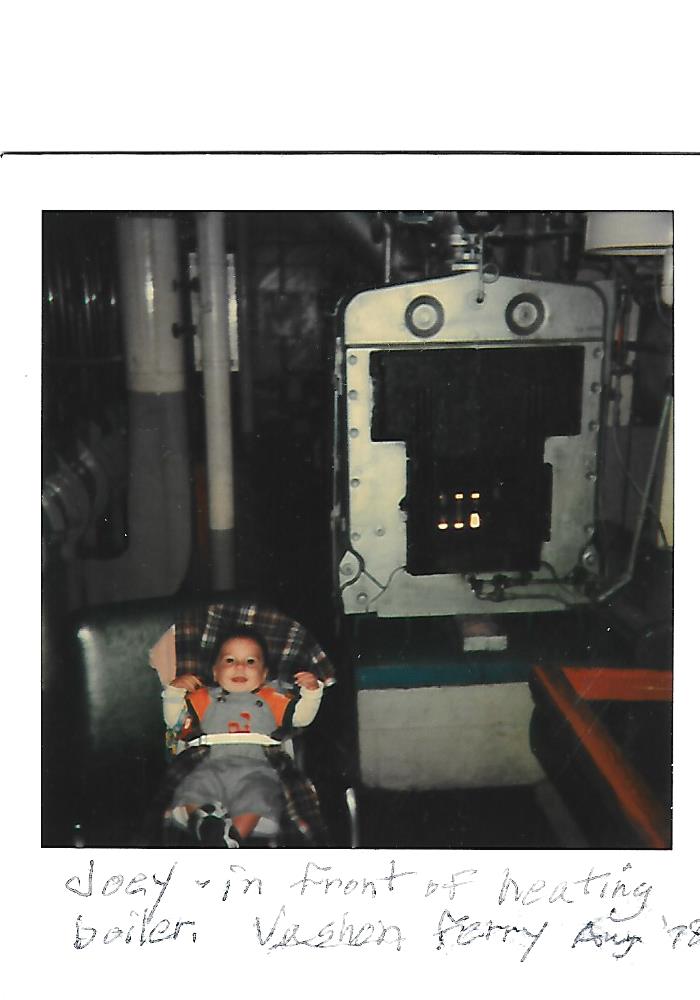

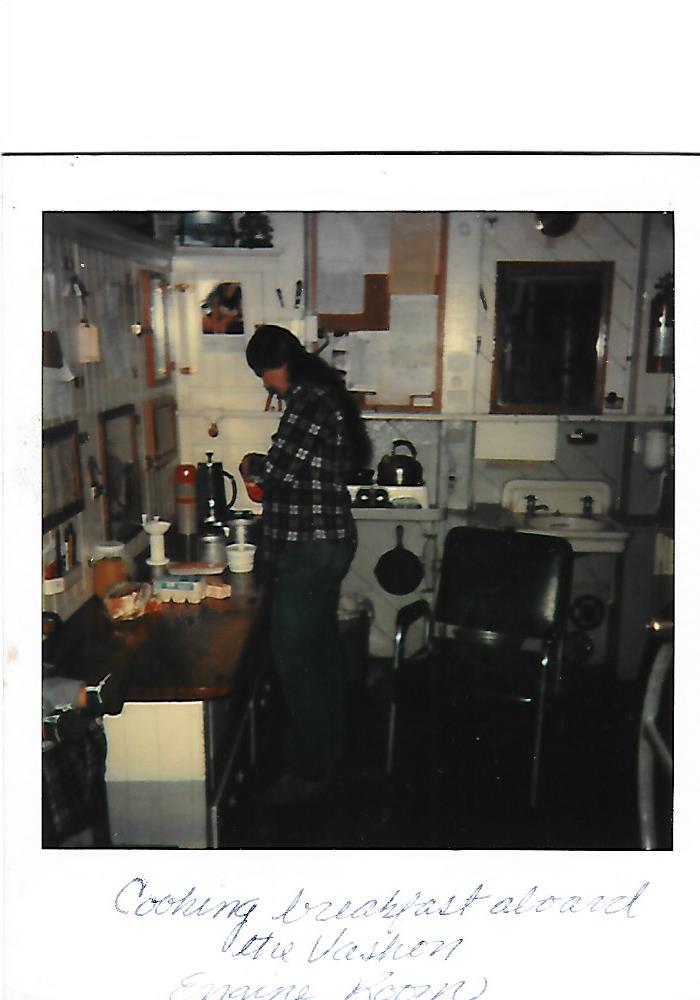

Four of us covered the watches during our 72-hour workweeks, crammed into six days–two oilers and two chief engineers, alternating watches. Another crew of four took over during our alternating week off. The intensity of the week-on duty was eased during tie-up watches at Anacortes by our living only a few miles away. During these watches, Victoria and Joey were regular visitors to the boat, arriving often with a home-cooked dinner or breakfast, reheated in the corner engine-room galley, equipped with a hotplate and iron frying pan and other basic cookware.

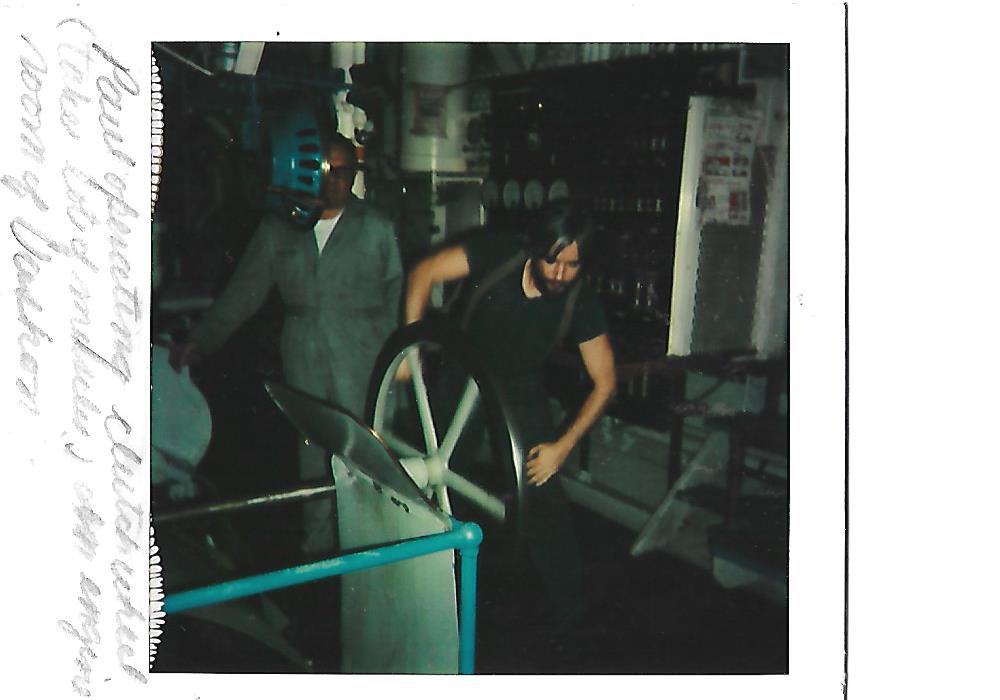

Though largely confined to the boat during the 72-hour week on, the oiler on duty was not without exercise. The “heavy duty” 900 horsepower Washington diesel, which sounded over the water a chortling rhythm easily distinguished from the surly growl of its more modern cousins, required frequent hand-oiling of its exposed moving parts. Direction, signaled from the wheelhouse through the engine-order telegraph, required the engagement or disengagement of a clutch at each end of the engine, connected with its respective propeller. Operation of the clutches came from a large handwheel, spun by the oiler. There was no need for gym attendance during the week off. Until one grew used to the to the physical demands of the old Vashon, the week-off duty might be partly spent resting sore muscles, before digging in the backyard garden.

In October, 1978, the seasonal “inter-island” run ended and the Vashon was sent down to Clinton, on the south end of Whidbey Island, where she would serve as an extra boat on the run between Mukilteo and Clinton. This meant a 5-day a week hour-long commute for any crew living in Anacortes, a disruption in the 1978 summer idyll I was prepared for. The hardest part was spending nights away from our new home and baby boy. We were getting to know Joey–beginning to crawl, his happy gurgling and chirping became joyful domestic background sounds. Then there was his dazzling smile, engaging his whole growing body. We had reached the point where it seemed inconceivable that he hadn’t always been with us.

Come November in Puget Sound country, the chilly, wet and gloomy season is upon us. Still in a state of happy wonder, we could easily chase the gloom, with plenty of firewood for the kitchen cookstove and the living-room heater, looking forward to the first major holidays in our newly acquired home. I’d enclosed the backyard in a cedar and wire fence and planted front yard trees. When newly-planted flower bulbs emerged in April and May, when the trees and lilacs bloomed, Joey might be walking, and stringing sounds together, heralding the onset of acquired language–a mystery I still contemplate.

On late Saturday afternoon of November 18th, we sat in the kitchen by the warmth of the cookstove for a pork-roast dinner, Joey between us in his highchair. A northeast wind was picking up, blowing in through the less than perfect seal of the back kitchen door. Before reluctantly leaving for work, I banked the living-room fire, then drove south to Mukilteo, where I’d deadhead on the ferry Elwha for a ride over to Clinton. The tie-up watch on the Vashon was uneventful. Morning dawned chilly.

On returning to our Anacortes home, looking forward to waking my family for Sunday breakfast, I rebuilt the fire in the living-room stove, then went upstairs to Joey’s room. Looking down into his crib, I peeled off the blankets. He appeared motionless, his face strangely white. I picked him up, observing he wasn’t breathing.

With a desperate hope that this was only a horrible dream, I began resuscitation on him as I’d learned in first-aid classes. Meanwhile, Victoria had awakened and was calling 911.

As we rushed out the front door to the waiting ambulance, the crew already working on our baby with a resuscitating device, I robotically closed the vents on the heating stove, now warm with the heated iron ticking. The ride in the ambulance was a blur. After an hour of numbed waiting, the doctor on duty at Island Hospital told us; “he didn’t make it.” A young redheaded nurse, her eyes reddened with tears, did her best to lend comfort.

An autopsy confirmed the doctor’s immediate conclusion that Joseph Patrick had died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. We’d heard of SIDS, but had chosen not to give it a lot of thought. We later learned it usually occurred at a few months of age, but can happen up until a year old. That it happens more to boys than girls. That a cold may be present, though the victim may be free of any signs of illness–in fact, was often in the best of health.

We had him buried in a tiny white coffin. Though both of us were very-much lapsed Catholics, we had a priest attend. As the months wore on, we learned that doctors now recommended babies sleep on their backs. We always put Joey down on his stomach, which we thought was the preferred way. Though the expert views were that the mysterious syndrome can in no way be consciously prevented, I couldn’t help but mull over “what ifs.” If we had laid him down to sleep on his back, instead of his stomach. If I hadn’t had to go to work that night, or had gotten home earlier. If we’d had central heating and the house better insulated (over the summer of 1979, with another baby due the coming October, I’d added insulation to the attic, backup electric heaters and new storm windows). But we read that the dreaded syndrome could just as likely happen in a well-equipped modern house.

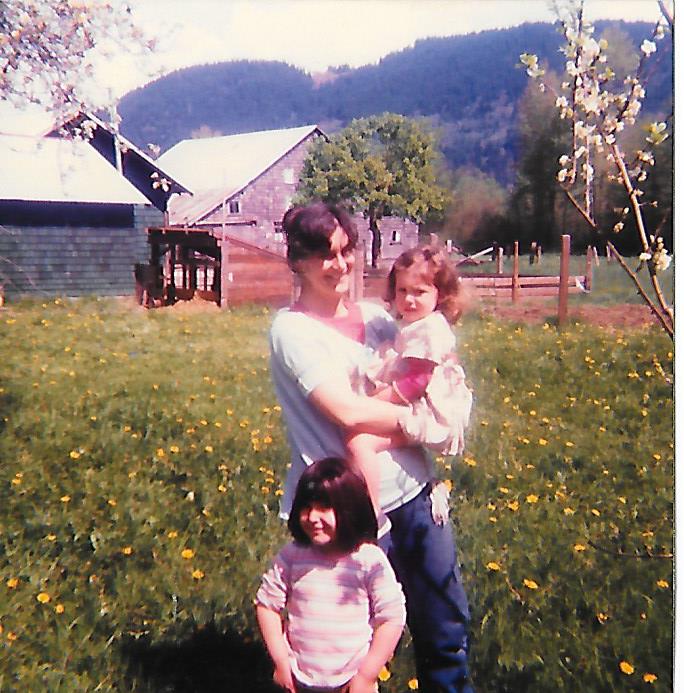

It’s a blessing we, more often than not, don’t know what the future has in store for us. If we did, life might be unbearable. Yet human resilience must never be underestimated. Within three years, we were the parents of two beautiful, healthy girls. I’d left the job on the ferries. We’d sold the house in Anacortes. We would carve out a new life on a small farmstead in the South Fork Valley, near the inland town of Acme, some 30 miles away. Life goes on. Helped along by the fact that we don’t fully know what the future will bring.

What a heart rending, beautifully told, story. I am so sorry. So much coming to an undeserving end. Richmond

Since Victoria and I met you at the “hippie house” on Ashworth Street in December 1972 (I think), our paths have frequently paralleled. And we both ended up as oilers on the old Vashon. You’re the only person I’m still in contact with who would remember the technique of spinning that oversize steel handwheel, to control the direction of the boat. Also hand oiling the rocker arms and valves up on the catwalk along the old Washington Estep engine. We also had the privilege of working under chief engineer Doc Clark (though you may have on another boat). No nicer boss did I ever have!

And you were there for us when we lost Joseph Patrick, 45 years ago. Thank you.

Paul