“Remember, Remember, the fifth of November!”

The old school-child chant of course refers to Guy Fawkes, sometimes dubbed as “the only honest man ever to enter the Parliament.” This date–celebrating the foiling of the 17th century plot to bomb the in-session workings of the English government–might also acknowledge a less sinister and more recent figure of history, who should be celebrated as one of the most honest men ever to run for President of the United States.

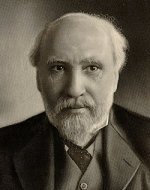

Eugene Debs ran for president first in 1900, as candidate for the Social Democratic Party, a reorganization of his old American Railway Union. In 1904, 19o8, 1912 and 1920, he ran as the candidate for the American Socialist Party–his 1920 campaign being run from the federal prison in Atlanta, while serving a sentence for opposing U.S. entry into World War One.

Eugene Victor Debs came from Terre Haute, Indiana. His French-Alsaceian immigrant parents ran a grocery store and imbued in their children a love of such writings as Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. Young Gene Debs’ early heroes included Patrick Henry and Tom Paine. He felt no attraction to foreign revolutionary movements and found Karl Marx to be “tedious.” Among his best friends was revered Hoosier poet, James Whitcomb Riley.

Starting work as a painter at age 15 for the Vandalia Railroad, Debs’ speaking and organizational abilities soon led him into leadership positions with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and editorship of its journal, The Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine. Though he rode many miles shoveling coal into the fireboxes of the big black locomotives, in his early 20s he was already spending more time travelling to organize fellow workers. And expanding The Magazine into the most widely-read labor journal of the time, adding features on history, law, and even a women’s section.

In his new found pulpit as associate editor, Debs stated the purpose of their union was “…to give to railway corporations a class of sober and industrious men…. To give to our superior officers trained and intelligent labor shall be our highest aim.” He spoke out against class conflict and lent no support to the great railroad strikes of 1877.

As the “guilded age” matured and rising industrial productivity worsened rather than improved the lives of the working people, Debs and other observers became disillusioned–watching corporate power becoming more concentrated in the hands of a rising class of the super-rich, more often than not aided–rather than regulated–by Washington, D.C.

The counteracting rise of a labor movement, dominated by the Railroad Brotherhoods and the American Federation of Labor (AFL), favored organization by craft. Efforts to better workers’ conditions led to futile strikes where various labor organizations often worked against each other–even as corporate owners and managers colluded for their own benefit. To Debs, the only solution was a labor union inclusive of all crafts–and ideally, without regard to nationality, gender or race. And so in 1890 he formed the American Railway Union (ARU).

As the worst depression up to that time paralyzed the economy in 1893, workers saw themselves and their families as the ones bearing the punishment for the excesses in speculation and stock overvaluing brought about by the gamblers and idlers of Wall Street.

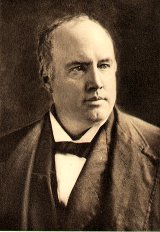

James Jerome Hill

The “Empire Builder” of the Great Northern Railway

courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

In May of 1894, The American Railway Union shut down the Great Northern Railway. The road remaining profitable, its owner James J. Hill had decreed wage cuts. In St. Paul, Gene Debs and Jim Hill met face-to-face, impressing each other as worthy adversaries, but neither willing to compromise. A suggestion was made to have the labor-management disputes arbitrated by a group of prominent St. Paul business leaders, led by flour-milling magnate Charles Pillsbury, a major shipper on Hill’s Great Northern line. Surprisingly, the ad-hoc jury of leading mid-western industrialists ruled in favor of the American Railway Union. Wage cuts were recinded and trains between the Twin Cities and Seattle began to roll again.

But while Debs and the ARU were relishing what was considered the first successful labor strike ever in America, trouble was brewing in sleeping-car maker George M. Pullman’s company town of Pullman, Illinois. With wages being pared while cost of groceries, coal and other essentials at Pullman’s company stores increased, in late May of 1894 the thousands of employees at the car manufacturing works, adjacent to the company town, staged a walkout. The newly-victorious American Railway Union voted to support the strike with a nationwide boycott on railroad sleeping cars operated by the Pullman Company. Debs had advise against the move, fearing it would destroy the union he’d so recently created. But as leader of a democratic organization, he felt obligated to support the rank and file of the ARU. He advised members to stay away from railroad property, to not impede passage of the mails, which would trigger an injunction. He stated, “We must triumph as law-abiding citizens or not at all. Those who engage in force and violence are our real enemies.”

The boycott on Pullman cars resulted in disrupted rail service nation-wide. Periodic outbreaks of violence occurred. The mainstream press vilified “Dictator Debs” and added to the clamor for intervention by the U.S. Army. President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, gave in. As many had predicted, including Debs, violence escalated once federal troops became involved. Cleveland issued an injunction, which Debs ignored, landing him and the rest of the ARU leadership in jail, then to 6-month prison terms.

The strike was settled with more losses than gains for the Pullman employees and for the railroad workers who supported them. Acquitted of conspiracy charges, Debs served six months in prison for violating a federal injunction. He emerged from his term a celebrity, who had defied the railroad companies, the President of the United States, and the U.S. Army. He now officially espoused Socialism, though his conversion had been long coming.

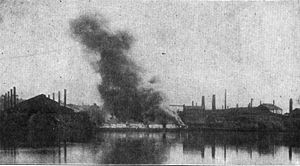

American Railway Union strikers (foreground) face the Illinois State Militia in Chicago.

from Wikipedia

By 1900, the American Railway Union had morphed into the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Reluctantly, Eugene Debs ran for president under its banner. The SDP evolved into the Socialist Party of America, with Debs as its standard bearer, gaining strength with each presidential election until 1912, by which time many of the reforms pushed for by the Populists and the Socialists had been co-opted by the Progressive wing of the Republican Party–its standard bearer being “Trust Buster” Theodore Roosevelt, known for his statement decrying the “malefactors of great wealth.”

Like Lincoln, Debs was a reluctant presidential candidate. He had also resigned from earlier positions with the Locomotive Firemen and the American Railway Union, thinking other men could better serve. When his resignation was refused by the membership, he tried to refuse the salary they offered, ending up negotiating for a lower figure.

Eugene Debs had his inconsistencies. He could be self-righteous and uncompromising. With a flare for the dramatic statement, he sometimes wrote things that would come back to haunt him. There was the “dynamite editorial” in 1885, and in 1900, his support for a plan hatched by Washington state Governor John Rogers to colonize the entire state with laid-off American Railway Union workers and other socialist sympathizers. A movement, he predicted, that would likely bring on the intervention of the U.S. Army (as had happened in the Pullman strike), wherein “300,000 patriots” would then confront the federal troops at the Washington state borders. Governor Rogers found himself having to “tone down” such statements to the likes of the Spokane Spokesman-Review, the leading newspaper of eastern Washington. And soon after, Debs began distancing himself from the “colonization” movement.

As with most of those who rise above the ordinary, Eugene Debs was both adored and vilified. But his words rang true for those who felt that neither the “mainstream” political parties nor labor organizations really represented them. His words deserve to live on.

I am not a labor leader. I don’t want you to follow me or anyone else. If you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of the capitalist wilderness you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into this promised land if I could, because if I could lead you in, someone else would lead you out.

While there is a lower class I am of it, while there is a criminal class I am of it, while there is a soul in prison I am not free.

Eugene Debs died in 1926, five years after a presidential pardon released him from his second prison term.